Really–the Honor Is Ours

It was a moment that called for a poetic home run, or at least a good cut at a high-floating fastball—maybe something like Robert Frost’s “good fences make good neighbors.”

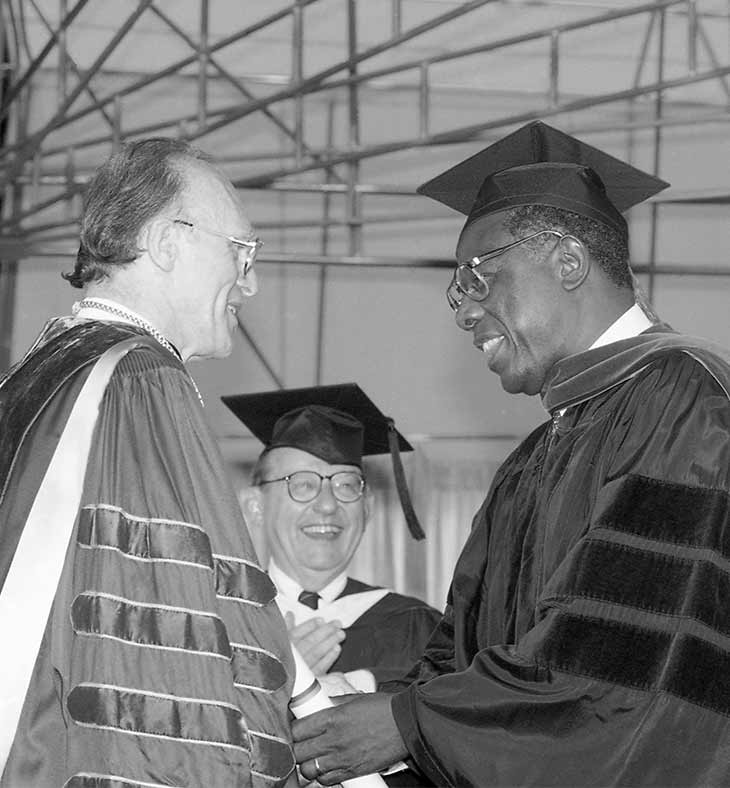

“Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron receives an honorary degree in 1995

The provost was draping a doctoral hood over the shoulders of Henry Louis Aaron—“Hammerin’ Hank,” the home-run king—at Emory’s Commencement in 1995. Somewhere nearby the ghost of President Warren Candler may have hovered in disbelief. Not only had his policy against intercollegiate athletics given way completely, but here was his beloved university honoring a professional baseball player, of all people, with the honorary doctor of laws degree, of all things.

Atlanta’s hometown hero, though, did not just swat baseballs magnificently. He lived with dignity and courage in the face of racist vitriol during his run at Babe Ruth’s career home-run record (which Aaron broke in 1974). Throughout his life, Aaron aimed to break down barriers and make civil rights a reality. This, Emory said, was worth recognizing with a degree that honored the law as well as the man.

As the university president read the accompanying tribute, the audience broke into applause at the line, “You showed good fences make good targets.” And thus, in awarding its highest honor to a man who hit balls over a wall, the university refreshed a tradition sometimes viewed as time-consuming and puzzling.

But Emory at that moment also raised in many minds the question about how it decides who receives an honorary degree. Scanning the universe of memorable achievement and the great men and women who populate it, how does the university’s gaze alight on this scientist and this poet rather than that musician or that politician? More curiously, why this Nobel laureate in medicine rather than that one?

Since the awarding of the first honorary degree by the University of Oxford, in the 15th century, the practice has implied a two-way exchange of esteem. We, the university, proclaim you to have earned a degree without all the study we normally require because you have done something great for humanity. You, in turn, elevate our status by associating with us. We are yours, as you are ours. You represent us as you inspire us.

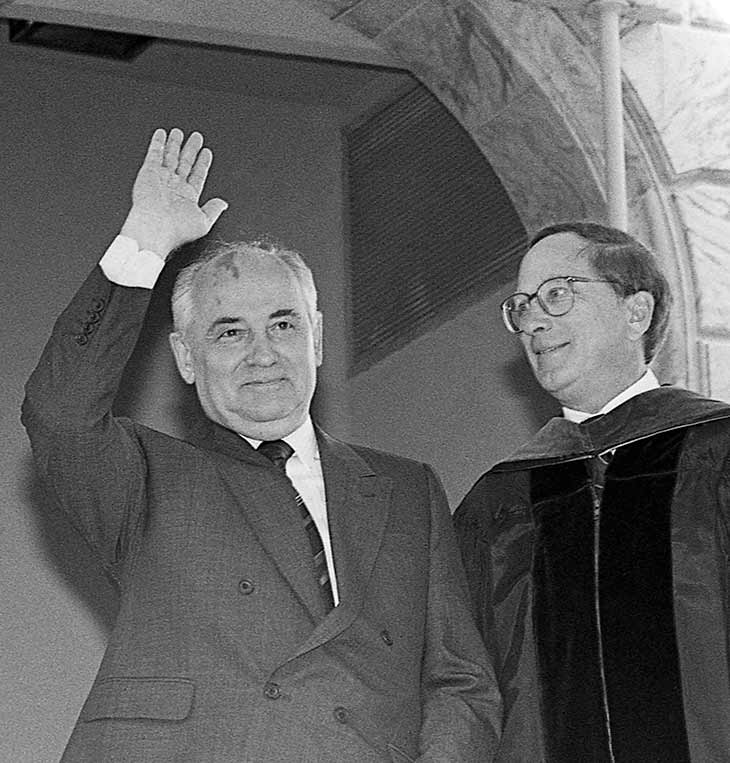

Mikhail Gorbachev at Emory’s Commencement in 1992

Recent history may suggest how this works. Emory was pleased, in 1992, to be one of only two US institutions to grant an honorary degree to Mikhail Gorbachev, whom Time magazine had recently declared the “man of the decade.” (The other was little Westminster College, in Missouri, where Winston Churchill had given his famous “Iron Curtain” speech.) Gorbachev had precipitated such change in the Soviet Union that he set in motion the end of the Cold War. The Emory Commencement at which he spoke provided the occasion for a mini-summit, as Gorbachev met beforehand with former President (and University Distinguished Professor) Jimmy Carter to talk about the work of The Carter Center as a possible model for the Gorbachev Foundation.

Honoring a political rock star, Emory gained a lot of press.

On the other hand, it can be tricky to recognize the best in their fields while requiring that their lives reflect the university’s mission and vision. Although the intense public interest in seeing Gorbachev required fencing the Quadrangle for the first time to preserve seats for the graduates and their guests, one faculty member complained that Emory was besmirching its honor by celebrating someone he considered an unrepentant Communist. Other faculty members have protested degrees for Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland; Ben Carson, brain surgeon and current secretary of Housing and Urban Development; actor and former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger; and Wernher von Braun, the rocket scientist who advanced America’s race to the moon but had been instrumental in the Nazi war effort as well.

It is difficult, however, to imagine protests against the earliest recipients of honorary degrees from Emory. The place was smaller then, the faculty largely of one faith if not one mind, and the students under strict parietal rules that left them well-disciplined.

Emory awarded its first honorary degree, a doctor of divinity degree (DD), in 1846, at the seventh Emory Commencement (the sixth with actual graduates). The recipient was the Rev. William H. Ellison, a Methodist minister and a leader in establishing higher education in Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia. He thus was typical of those whom Emory recognized throughout the 19th century for their contributions to the church and education.

Warren Akin Candler

Indeed, many of the honorees (Oxford University prefers “honorands”) through Emory’s first seven decades were Emory faculty members and presidents. Two of those—presidents Alexander Means and Warren Akin Candler—received multiple degrees. Means, a medical doctor and minister, received the DD in 1854 and the LLD (doctor of laws) in 1858, even as Candler has the distinction of being the only person to receive three honorary degrees from Emory, which was also his alma mater.

Things have changed. The current guidelines of the Honorary Degrees Committee note that only in “extraordinary circumstances” will it consider “persons who have spent the greatest part of their careers as members of the Emory faculty or administration.” Still, the university occasionally makes exceptions, as in conferring honorary degrees on more-recent Emory presidents Sanford Atwood (1978) and James Laney (1994), as well as Emory’s first provost, Billy E. Frye (2015). (In a nod to their contributions to the university, Elizabeth Atwood and Berta Laney also received degrees when their husbands did.) Most recently, Natasha Trethewey, formerly the Robert W. Woodruff Professor of English and Creative Writing, received the doctor of letters degree before giving the Commencement address in 2017.

In the early days, when travel was more difficult, the conferral of an honorary degree required only a vote of the trustees. Yun Chi-Ho, the first international student to graduate from Emory and a national leader in his native Korea, could not travel to Emory to pick up his LLD degree in 1908. No matter—he still has his place on the roll of honor.

Kiyoshi Tanimoto

Nowadays, except for the rarest of reasons—death being one of them—recipients of honorary degrees have to show up to receive them. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a 1940 graduate of the theology school, Methodist minister, and survivor of the Hiroshima atomic bomb who established the Hiroshima Peace Center, died just before the 1986 Sesquicentennial Celebration at which he was to receive his DD degree with nine other distinguished alumni. His widow came to Glenn Memorial for the convocation and accepted the honor on his behalf.

At other extraordinary times, the university travels to the recipient. Sir John Carmichael, a Scottish businessman and longtime eminent supporter of the Bobby Jones Scholarship program, was in failing health when he planned to visit the Augusta National Golf Course for the 1994 Masters Golf Tournament. Emory kindly obliged his inability to return from Scotland for Commencement the next month and presented his degree at the Butler Cabin on the penultimate day of the Masters in the presence of that year’s class of Bobby Jones Scholars.

Robert Woodruff, whose place in Emory history is unique in many ways, declined an honorary doctorate when the trustees first offered it, but he finally agreed to accept it 30 years later, on December 6, 1979—his 90th birthday. President Laney handed him his diploma during a small celebration at Woodruff’s Ichauway Plantation, where the gathering included former Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr.

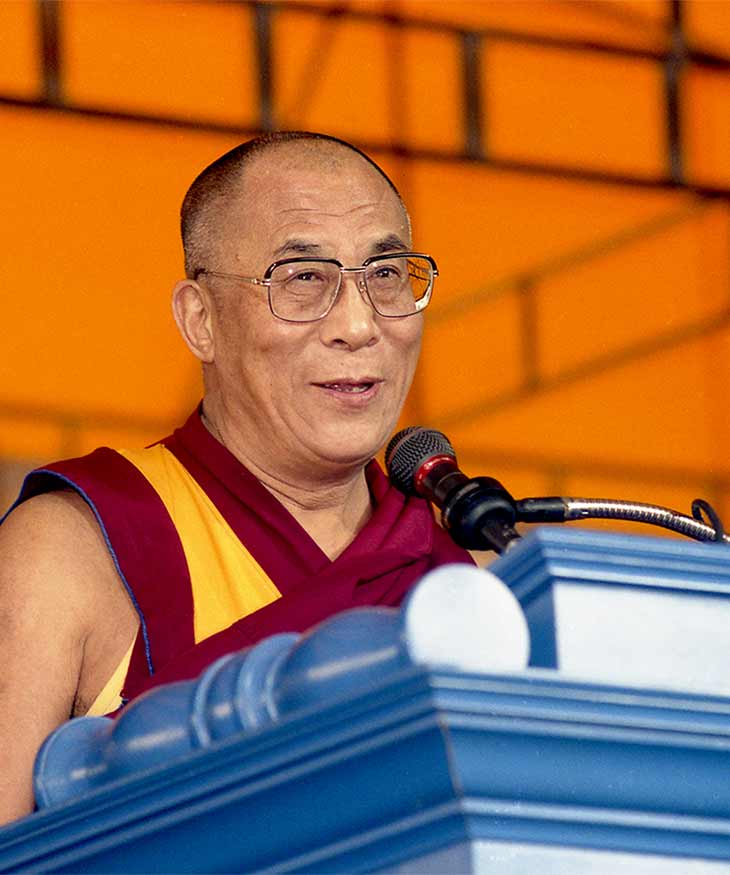

His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama addresses Emory’s 1998 Commencement

Marvelous as an honorary degree may be, sometimes something else is called for. When His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama visited Atlanta in 1995, organizers of the visit asked Emory to host one of the planned events. On short notice, it was impossible to work through the process of consideration by the Honorary Degrees Committee, consultation with the University Senate, and approval by the board of trustees.

Instead, President Bill Chace commissioned the President’s Medal, to be conferred on distinguished university guests who have enhanced the prospect of peace or enriched cultural achievement. After bestowing the President’s Medal on the Dalai Lama in 1995, the university invited him back in 1998 to give the Commencement address, help inaugurate the Emory-Tibet Partnership—and receive the DD degree.

Three other persons have received both an honorary degree and the President’s Medal when circumstances fit the conferring of one honor years after the other: Congressman John Lewis (medal 2000, LLD 2014); former President Jimmy Carter (LLD 1979, medal 2015); and public health superstar William H. Foege (ScD 1986, medal 2016).

Carmen de Lavallade at Emory’s Commencement in 2018

The university suggests its values and priorities with honorary degrees. For instance, the 14 Nobelists with Emory honorary degrees include 10 peace laureates, two in literature, and one each in economics and medicine. Although public servants and philanthropic business leaders tend to outnumber all others, writers also abound among the honored—appropriate for a university with a top-ranked undergraduate creative writing program.

The first writer honored was Joel Chandler Harris (1902), and the most recent was former US Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey (2017). In between came Eudora Welty (1982), Ursula K. LeGuinn (1986), Athol Fugard (1993), Wole Soyinka (1996), Alfred Uhry (2002), Seamus Heaney (2003), Melissa Fay Greene (2010), Rita Dove (2013), and Salman Rushdie (2015). Other artists have included choreographers (Dorothy Alexander, 1986; Carmen de Lavallade, 2018); visual artists (Benny Andrews, 2007; environmental sculptor George Trakas, 2011); architects (Philip Trammell Schutze, 1979; Paul Rudolph, 1981; and Michael Graves, 2013); and musicians (Robert Shaw, 1967; Van Cliburn, 1994; and Robert Spano, 2009).

Tommie Dora Barker

The university also proclaims other commitments through honorary degrees. With an entirely male faculty and student body well into the 20th century, Emory took until 1930 to award an honorary doctorate to a woman, Tommie Dora Barker, the founding dean of the university’s library school, but that honor signaled that women’s intellect now helped shape the institution. Not until 1970 did the first African American receive an honorary degree—Benjamin Mays, the legendary president of Morehouse College. This was the same year that Emory College decided to establish what is now the Department of African American Studies.

Occasionally, too, the university may confer an honorary degree to atone for its lapses. In 2000, Emory awarded the ScD degree to Leila Daughtry Denmark, a pediatrician who was then 102 years old and would continue practicing for another year. She had been the first female physician—indeed, the first physician—on the staff of Egleston Hospital when it opened on the Emory campus in the 1950s. She would live to the age of 114.

In 2000, diminutive but standing straight, and smiling on the stage to hear her tribute read, this centenarian must have basked in satisfaction: the university that had discouraged her from applying to its medical school in 1924 because she was a woman was now conferring belated but well-deserved recognition—“with gratitude,” the citation said, “that Emory at last can call you daughter.”

Though the process of nominating, evaluating, and choosing candidates for honorary degrees has changed slightly during the years, the Honorary Degrees Committee of the University Senate always has in mind two overriding criteria: is the nominee at the top of his or her game (whether jurisprudence, physics, or baseball), and does the nominee play the game in a way that reflects the highest values of the university? For everyone from William H. Ellison in 1846 to the honorees in 2018, the answer clearly was yes.